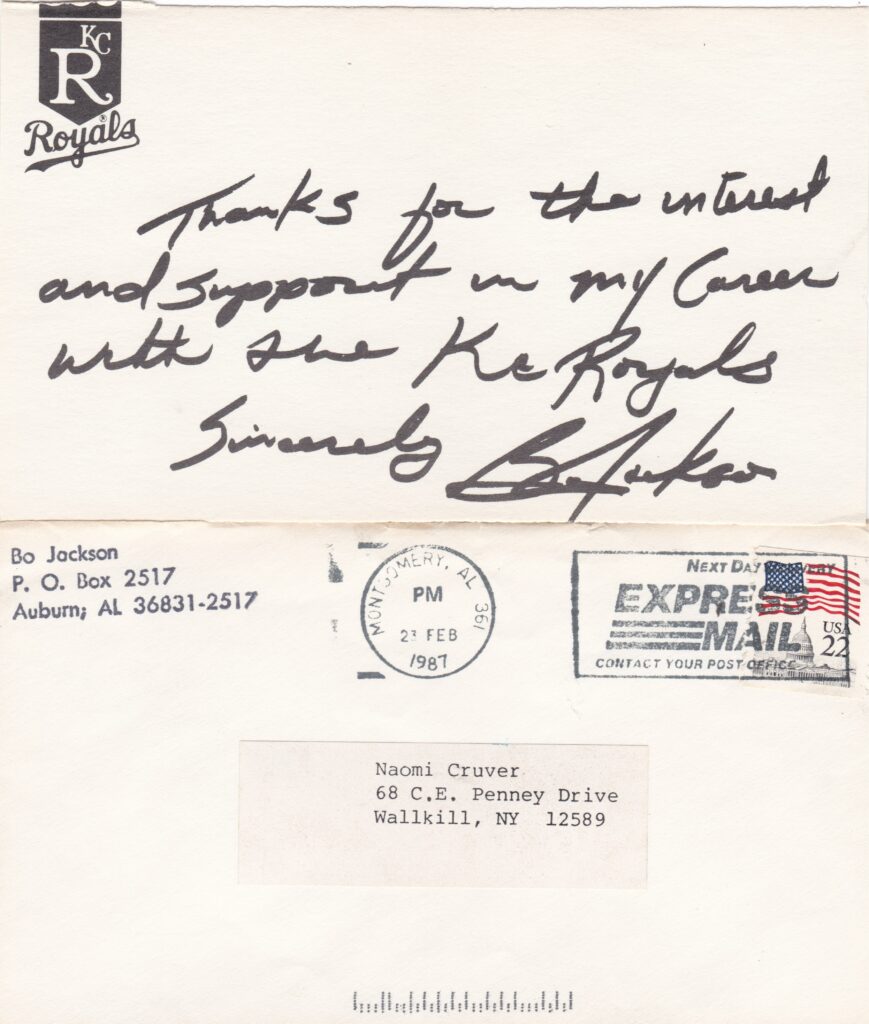

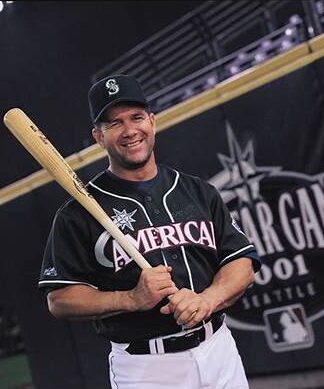

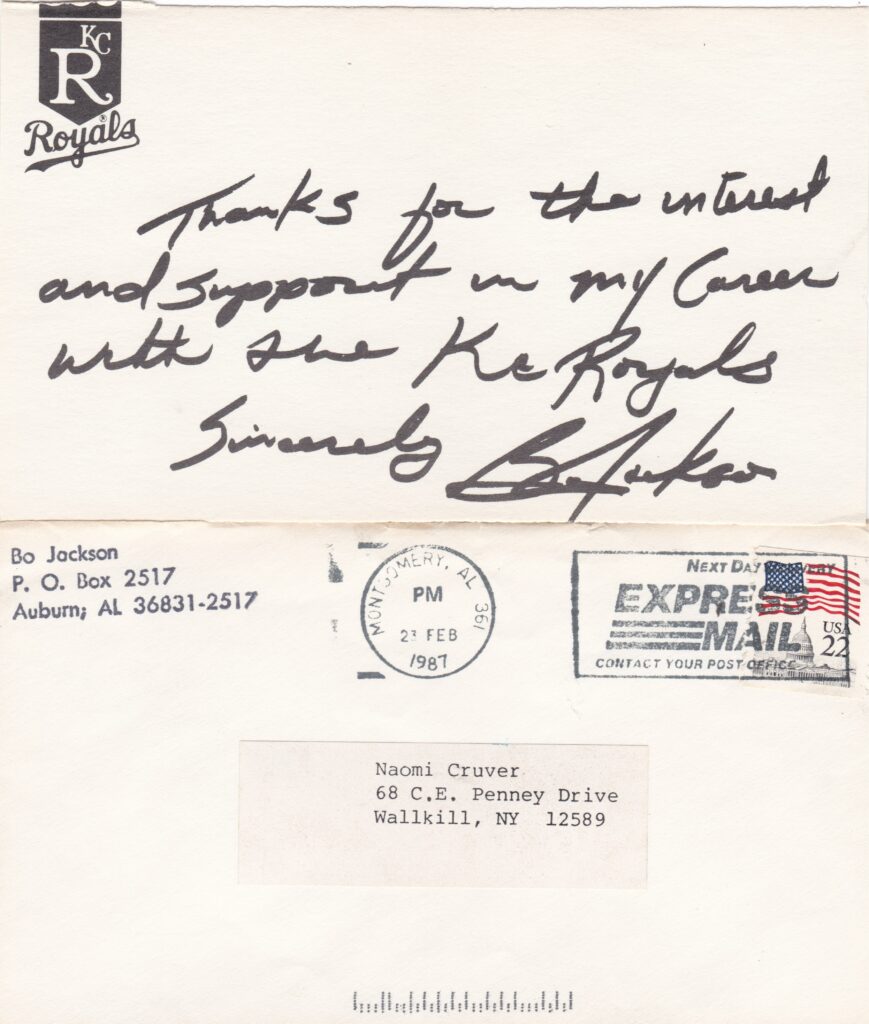

In baseball a five-tool player hits, runs, throws, fields, and hits for power. Bo Jackson put all five tools on display during his 8-year big league career. His most memorable throw was on June 5, 1989 against the Seattle Mariners.

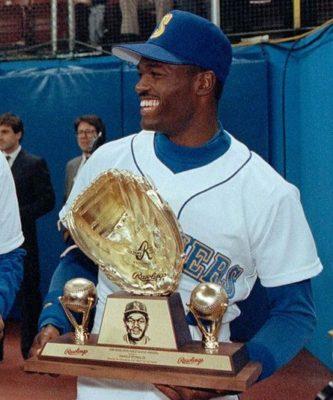

Bo’s game-saving heave came in the bottom of the 10th inning in a 3-3 tie at Seattle’s Kingdome. The toss cut down Mariner speedster Harold Reynolds at the plate, kept the game knotted, allowing the game to continue until the Royals pushed across two in the 13th to win the game.

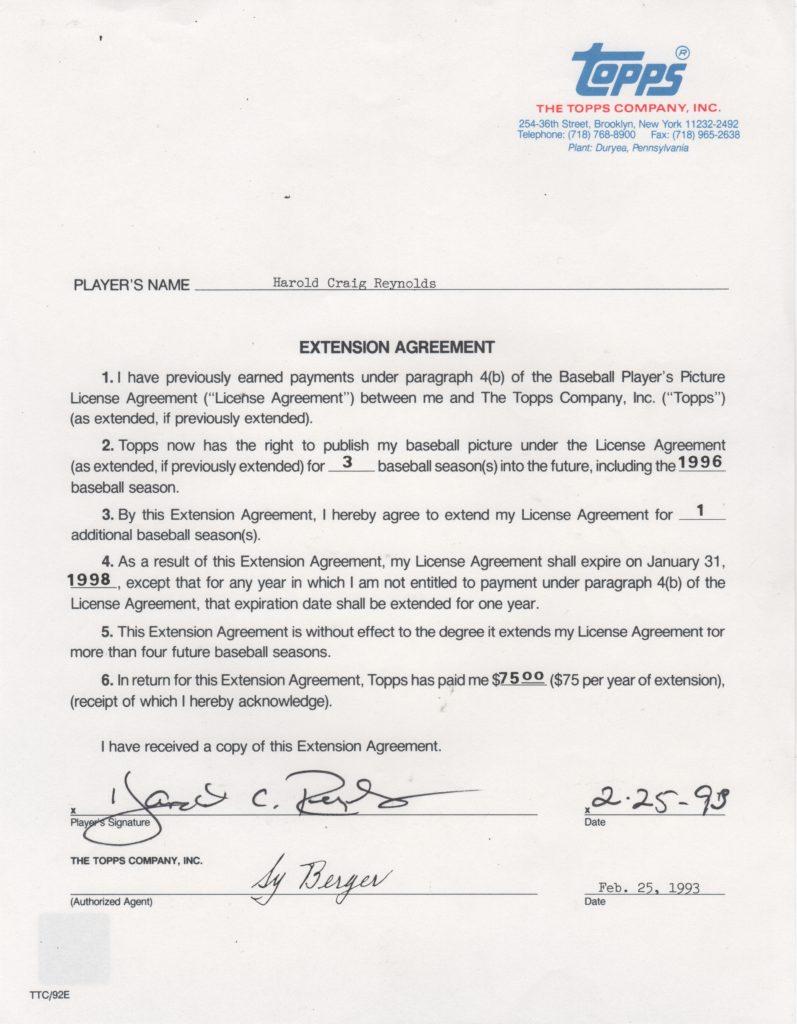

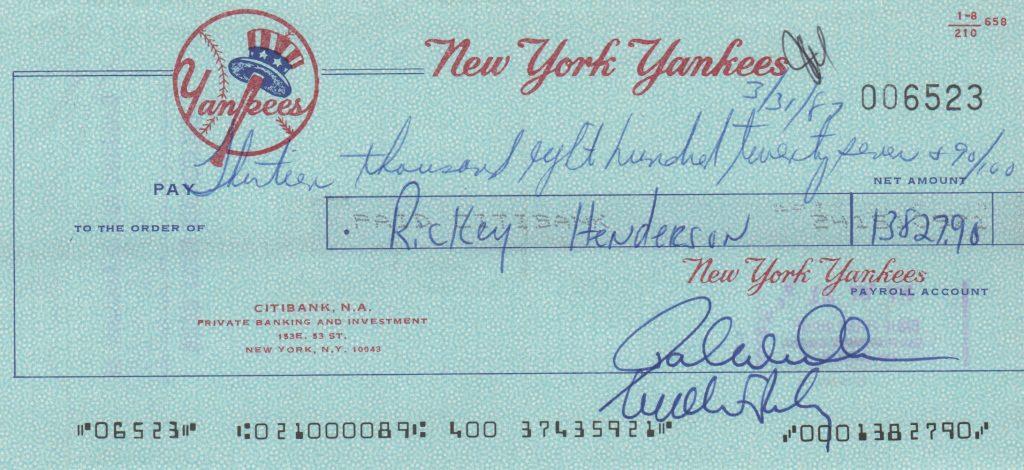

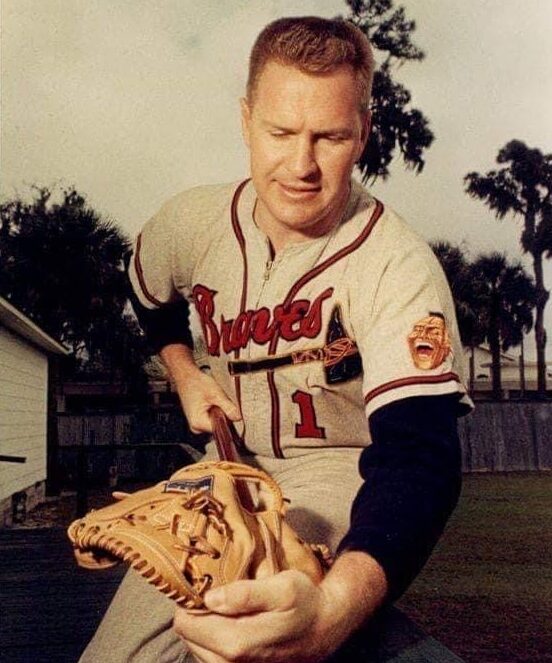

The American League stolen base champ in 1987 tells the story.

“So I’m on first base, Scott Bradley is at the plate. I’m stealing on the play and he hits it into the left field corner. I’m running and I see where Bo’s at and I see where the ball is at and I’m like, ‘Game over.’ I’m flying full tilt and as I come around third, Darnell Coles was the next hitter. He’s standing there going, ‘You gotta slide! You gotta slide!’.

“And I’m in my head going, ‘Slide? What’s he talking about? Ok I’ll give it a courtesy slide, you know?’.

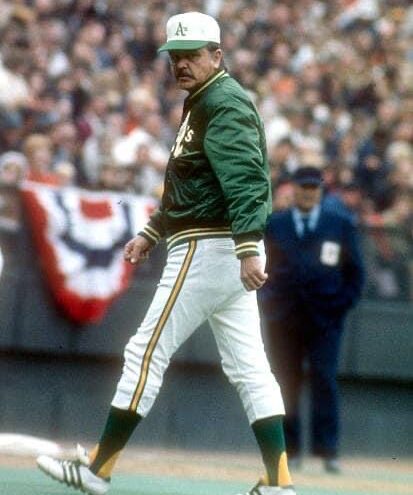

Bob Boone the catcher had actually taken his mask off and starting walking towards the dugout. So I’m seeing Darnell telling me to slide and I’m seeing Booney start to walk off, and I’m thinking, ‘Who’s wrong here?’.

I go, ‘Ok, maybe Boone’s trying to deke me so I better keep going hard.’ But he was walking to the dugout. And so next thing you know, the ball, Bo gets it, catches it barehand one hop off the fence, spins and throws it in the air. All the way. No stride, no recoil step. He didn’t have time. He just caught it and threw it like this all the way in the air and got me.

“I mean, this is the greatest play in the history of baseball.”