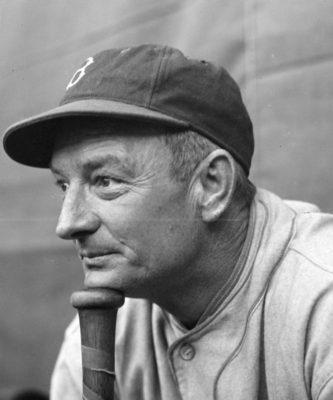

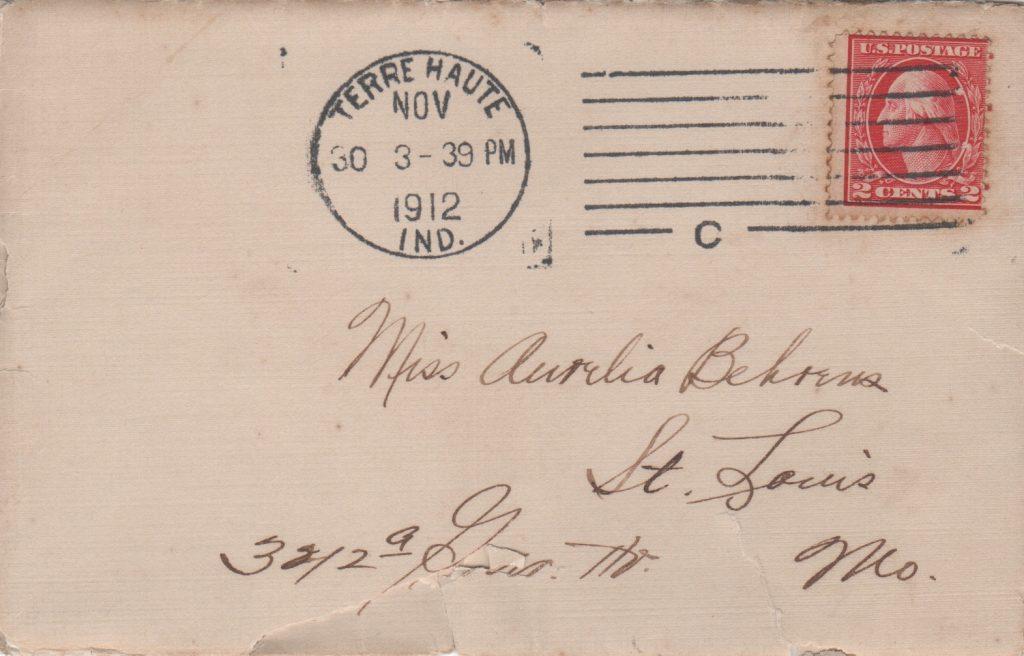

Max Carey

| Birthdate | 1/11/1890 |

| Death Date | 5/30/1976 |

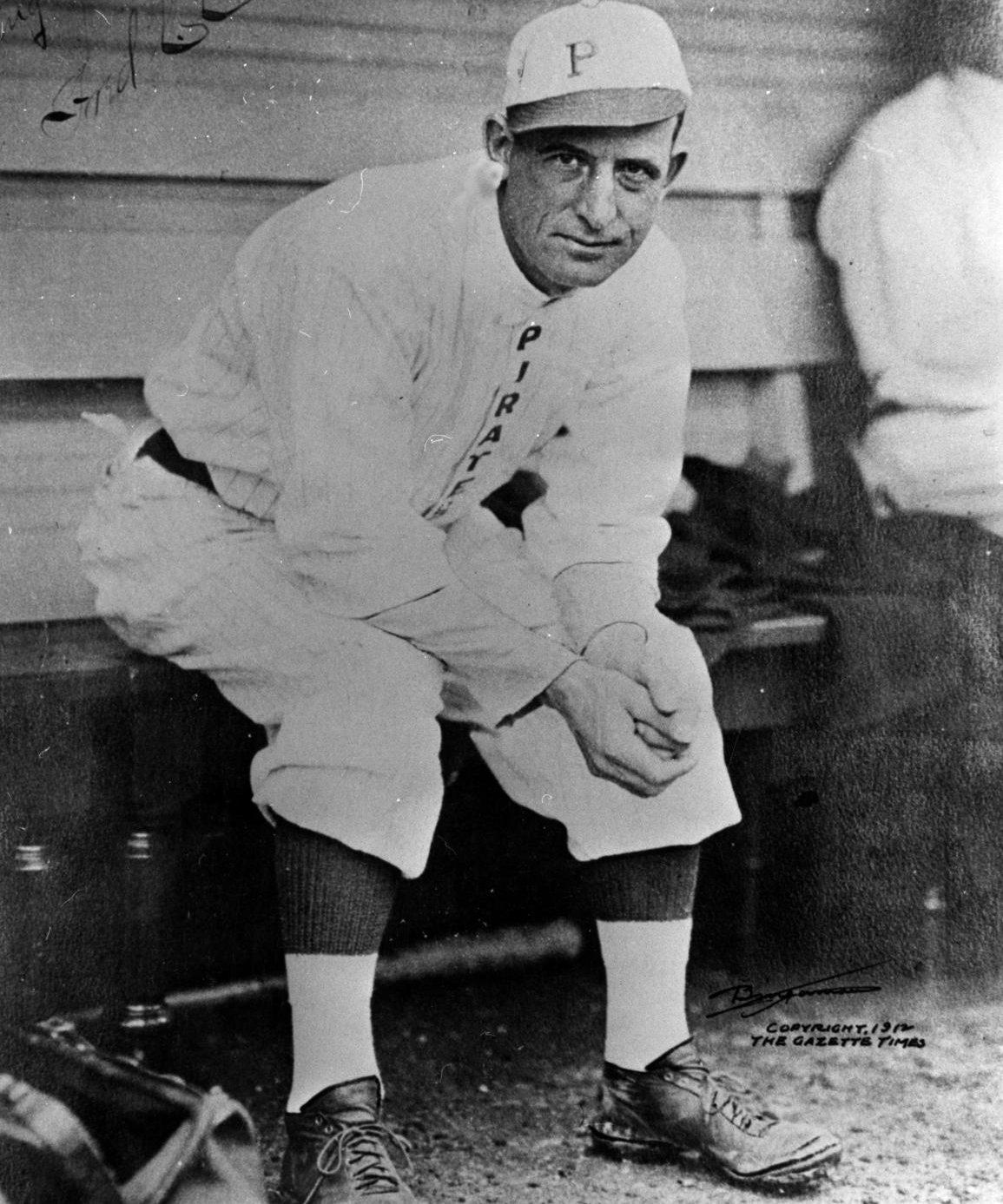

| Debut Year | 1910 |

| Year of Induction | 1961 |

| Teams | Dodgers, Pirates |

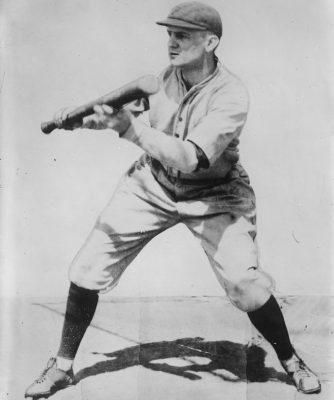

| Position | Center Field |

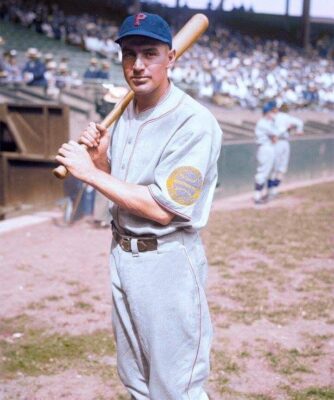

Max Carey led the National League in stolen bases ten times during his 20-year career. He held the NL career mark until Lou Brock broke it in 1974.

Leave a commentIn the collection:

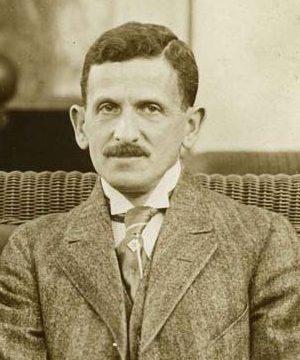

Max Carnarius changed his last name to Carey to protect his amateur status

Carey held the NL career record for stolen bases until Lou Brock broke it in 1974

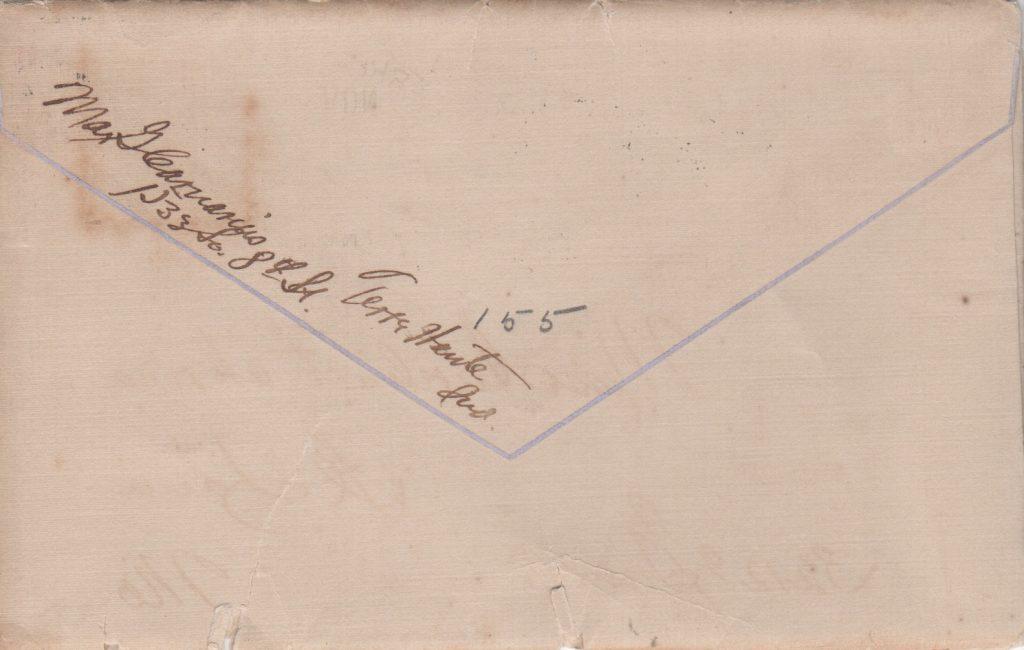

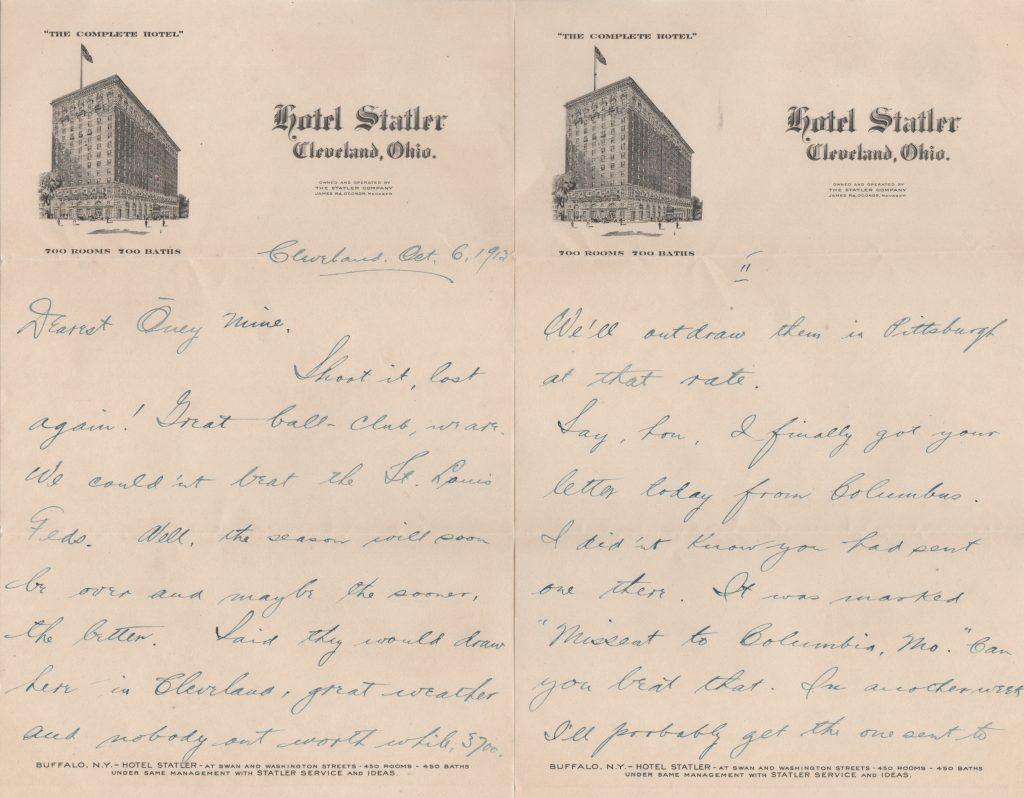

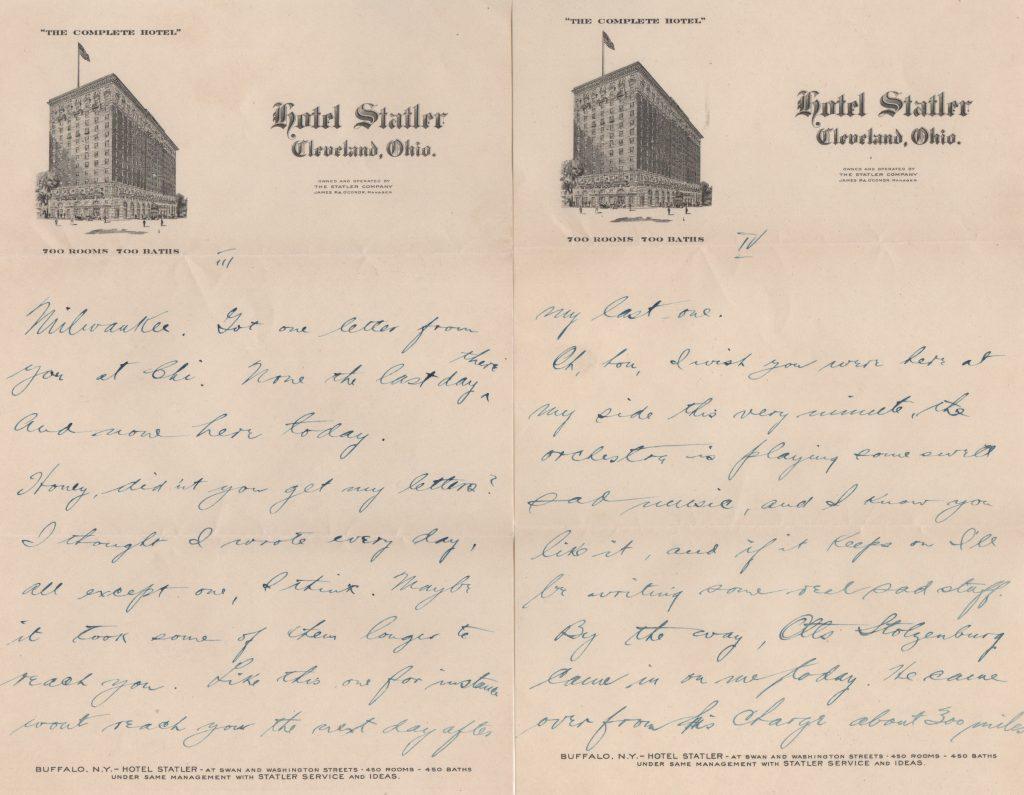

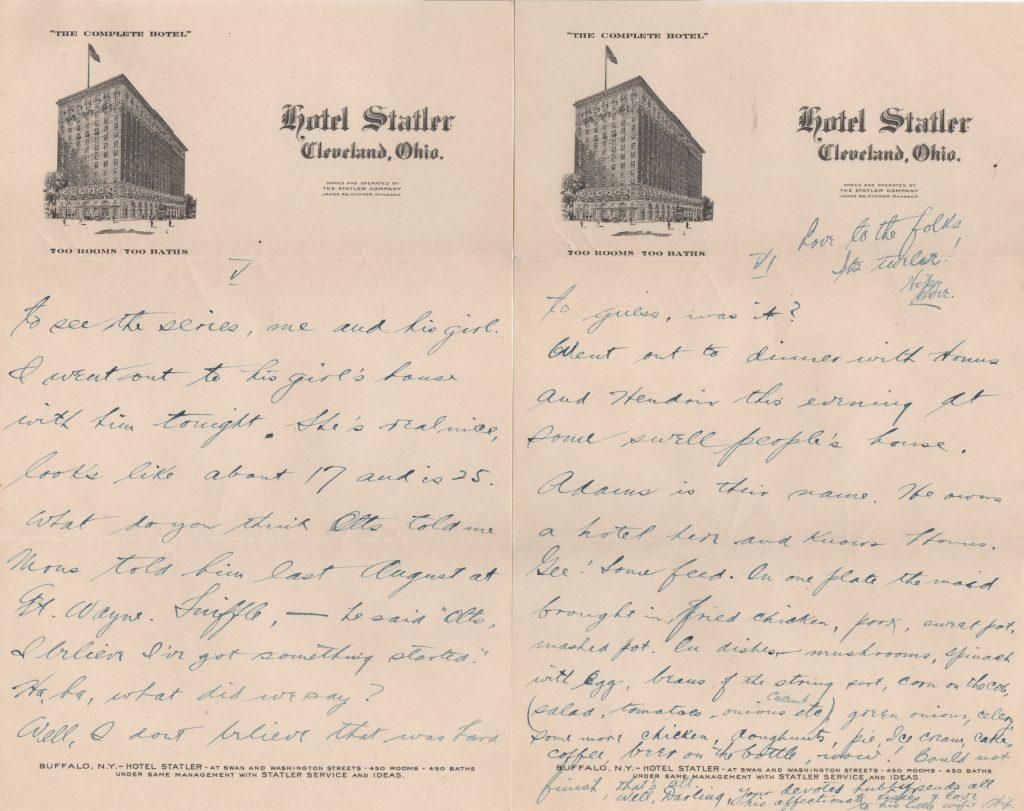

Carey kept in touch with his wife during the season through letter-writing

Carey wrote this letter to his wife on the last day of the 1913 season

Carey's tone in the letters is that of a loving and devoted husband

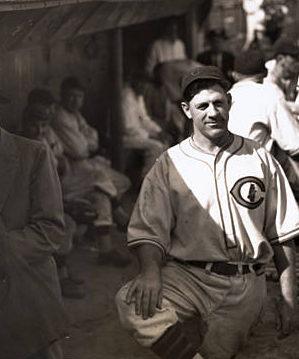

Honus Wagner befriended Carey when the speedster joined the Pirates in 1910

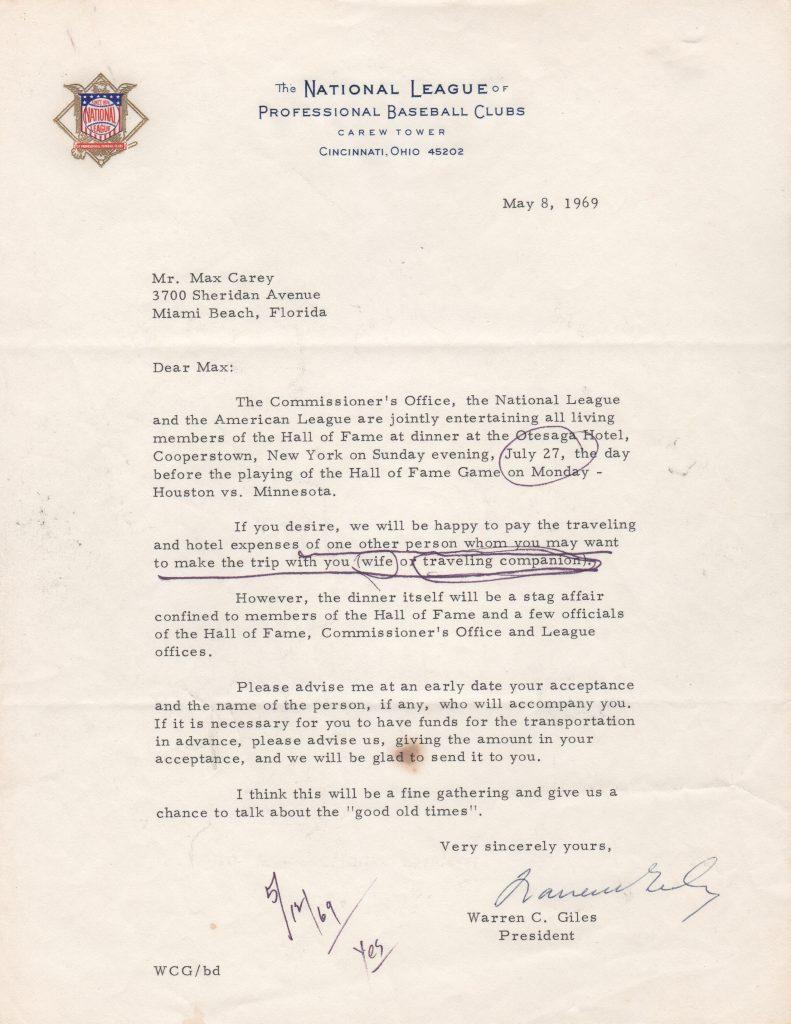

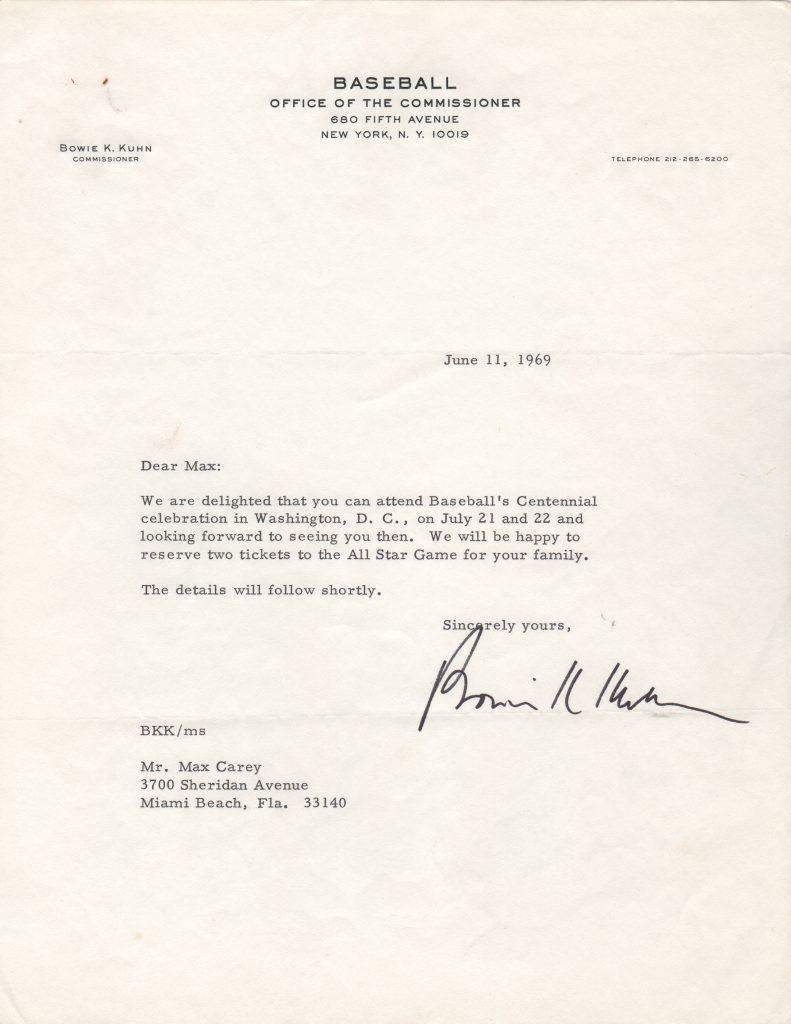

As a Hall of Famer, Carey got invited to many Cooperstown parties

Baseball threw a centennial celebration in 1969 - Max Carey attended